How does reception theory explain shifts in audience interpretation of media and filmic texts?10/5/2020 Reception studies, which examine how audiences consume and respond to film, was “only marginally developed within film studies” (2018, Biltereyst, Meers, p.22) during the twentieth century. Nevertheless, theories emerging in the 1980s increasingly acknowledged viewers as ‘active’ participants in the decoding of media texts; Stuart Hall suggested that an individual reading of a text is affected by personal experiences (2006).

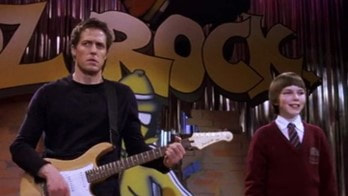

In his essay Crossing Out The Audience, Martin Barker noted a lingering presumption that the “ontological characteristics” of a film “inscribe themselves onto their ‘spectators’” (2012, pp. 188-189). However, Hall identified three different standpoints in relation to audience interpretation of film (2006). In a dominant reading, an individual decodes a text in the way that the producer intended, because they share the same ideological values; in a negotiated reading, an individual can recognise sub-textual encoding, even if it doesn’t fully align with their personal ideology; in an oppositional reading, the viewer’s ideological positioning directly opposes the producer’s perspective, and they therefore decode the text as offensive or unacceptable. Socio-political, economic and cultural factors are likely to determine which readings are adopted by consumers of media and filmic texts at any given time. With reference to Hall’s paradigm, this entry will consider how audience reception of About A Boy (2001) may have altered since the time of its release. Contemporaneous reviews promoted the film as a light-hearted but poignant drama in which carefree bachelor Will is reluctantly drawn into the uncomfortable world of quirky preteen Marcus. The sequences detailing Marcus persistently turning-up at Will’s house uninvited were originally portrayed by audiences as comedic and necessary to the plot; little attention was drawn to potential safeguarding risks that would be highlighted with today’s amplified focus on child protection. A chirpy piano melody underscores a rapid sequence of medium shots of Will and Marcus watching TV on the sofa, encoding a cheerful atmosphere; in 2002, a dominant reading of this segment might perceive with satisfaction, that Marcus has found his way into Will’s life. Hall outlines how a viewer taking up an oppositional stance “retotalize[‘s] the message within [an] alternative framework of reference” (2006, pp. 172-173); in 2020, an audience with a heightened awareness of safeguarding procedures may view Will’s behaviour as borderline. Another narrative thread, which might now illicit a negotiated or oppositional reading, is Will’s ‘hunt’ for single mothers in order to conduct casual affairs. His droll voice-over, lamenting his lack of knowledge about where to find lone mothers, overlays a medium-long shot in which he approaches a young mother and her child in a supermarket aisle. Whilst the comedic narration may have excused Will’s predatory behaviour in 2002, modern audiences, acutely conscious of patriarchal power abuses, in the wake of #MeToo, might not be as easily swayed by Will’s smooth exposition. As a tracking shot captures Will locking onto a poster for a single parent support group (SPAT), the upbeat tone of the score injects the scene with a feeling of excitement, heralding a new chapter in his search for casual sex. The jaunty notes continue as he makes his way to SPAT’s meeting place in a rented basement, whilst a low-angled shot depicts him descending into the dark cellar as he fantasises about getting beautiful single mothers ”roaring drunk” as a precursor to sleeping with them ; in a modern context, a man seeking out sexual gratification from vulnerable women in this way is likely to receive harsh judgement. As such, Hall’s reception theory model could be used to predict how audience evaluation of filmic texts may fluctuate. Reference List Barker, M (2012) ‘Crossing Out the Audience’, in Christie, I (ed) Audiences. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, p. 187-205. Biltereyst, D and Meers, P. (2018) ‘Film, cinema and reception studies’, in Giovanna, E and Gambier, Y (eds) Reception Studies and Audiovisual Translation. John Benjamins Publishing Company, p.21-41. Hall, S. (2006) ‘Encoding/Decoding’, in Durham, M and Kellner, D (eds) Media and Cultural Studies. 2nd edition. 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed